Friday Finance: beating the house

Is it possible for the average bloke to do better than the S&P 500?

I often refer to the S&P 500 on these pages. It is an index of the largest 500 US stocks.

This is because, as far as investing is concerned, the S&P 500 is The House. It is the standard by which all other investments are measured.

This is not because an index fund based on this particular index is necessarily the best. One that is even broader, encompassing thousands of stocks or perhaps including international stocks, might better suit some investors.

Rather, the S&P 500 is the house because (a) it is the biggest game in town, featuring the world’s largest companies, (b) it is the most well-known index, (c) it has excellent statistics and charts available going way back, and (d) its size and importance makes it a good proxy for how well stocks perform in general. Many other stock market indexes closely correlate with the S&P.

If you want to know how well some other investment option has historically performed, you must ask: compared to what? And the ‘what’ will be the S&P 500, just as you’d compare the carbohydrate content of sorghum against wheat or the strength of chromium against steel. It is the bog-standard investment everybody knows and understands, it’s been around for a long time and it is as mainstream as you can get.

The Holy Grail of investing is to beat this index.

We know that a few manage to do it – Warren Buffet, some lucky geeks who sold their crypto just in time and so on. It is physically possible.

We also know that very few actually manage to do it. The average investor underperforms the S&P because he buys high and sells low rather than buying and holding for the long term.

In this post we’ll analyze various investment options spruiked by some as index-beating miracles and see how well they do. The results may be surprising.

We’ll skip precious metals as we’ve covered that extensively elsewhere.

Real estate

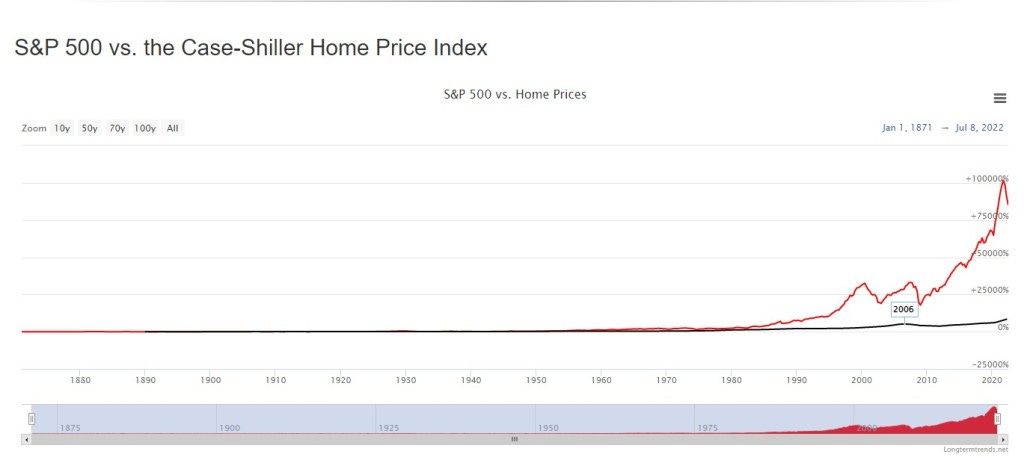

This chart compares average US home prices against the S&P:

The results speak for themselves.

To be fair, some housing markets have grown much more than in the US, especially big cities in Canada and Australia. There are various factors leading to that. There are also places where housing has done worse, i.e. Japan.

There are many differences between these asset classes that make them difficult to compare. For example, you can’t get dividends from a house. You can’t rent out or live in a share, much less grow veggies in the backyard. Not many people panic-sell a house if prices fall. They are taxed differently depending on the place. In Australia, someone earning a very high income can pay no more tax than someone earning an average income if he has investment properties and a good accountant. That’s in dollar terms, not percentage-wise.

In the end, whether each of these suits you depends on your circumstances, but we cannot say that real estate is likely to beat the house over the long run.

Small-cap stocks

There is an old idea that small-cap stocks are more volatile than big-caps but offer greater returns in the long run. An even-weight index fund (which tracks companies equally rather than proportionally by market capitalisation) or a fund that specifically tracks only small caps might therefore beat the house, if given enough time.

I found a chart going back to 1978 comparing different indexes by market cap. See second image for an explanation.

Hmm, very interesting. Here the black line (Wiltshire Large-Cap) is the closest equivalent to the S&P 500 and it is just beaten by small caps, beaten a bit more by mid-caps and mogged by the broadest index which covers 5000 companies.

The micro-caps didn’t do too well.

I also looked at similar Vanguard funds but in the smaller time frame available for comparison they were neck and neck.

I reckon, all things being equal, it’s good to go for the broadest index fund you can find, rather than just one that covers the S&P. American investors, for example, might choose to invest in the VTI which covers over 4,000 stocks. Be aware that the overall difference will still correlate strongly with the S&P because of the weighting towards the big stocks.

Specifically investing in smaller stocks or an equally-weighted index seems riskier without strong evidence of increased return. I reckon, in general, you should just go as broad as possible.

The ‘all things being equal’ part refers to what products you have easy access to and the fees they charge. You can only do what you can do. The Australian-domiciled international fund I invest in contains a bit under 1,500 stocks. I’d like something broader but that would involve time and hassle for a result that would probably be about the same.

When discussing general stock market activity on these pages, why do I almost always use the S&P 500? Why don’t I refer to the broader VTI or Wiltshire 5,000 instead?

Simple. Most of the stats I can dig up use the S&P 500. That’s it.

There’s a reason science experiments are mostly done on rats rather than bandicoots. Where the hell are you going to get bandicoots?

International stocks

For most people around the world, having some international exposure is a no-brainer. All but one country have markets that are too narrow slivers of the global market to be well diversified.

For Americans it’s a bit more complicated, because the S&P 500 is a large proportion of the global market. How much exactly I was unable to find.

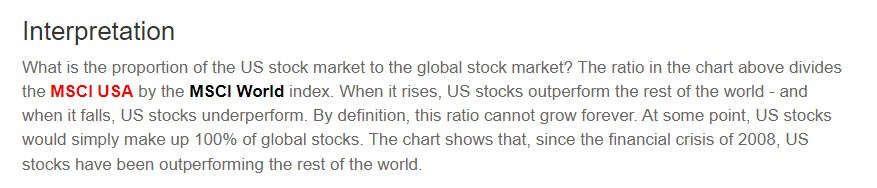

Anyway, once again this is one of those rare cases where I located a non-S&P index with which to make a comparison, thus undermining the point I made a moment ago about how ubiquitous S&P stats are. Oh well. This is free content, what do you expect? Let’s look at US vs world stocks since 1970, with the MSCI USA roughly standing in for the house:

Please note that MSCI World includes the US plus 22 other developed countries, so there is both overlap and many countries that are not considered here.

Well, there you have it. Looks like international stocks sometimes beat the US and sometimes don’t. A bit of overseas exposure may offer Yanks some diversification to smooth the jagged line. It would have limited growth over the last 13 years but would have been a consolation during some hard times before that, and likely will again play this role in the future. Nobody really knows. Make up your own mind, I guess.

As for us garlic-smelling foreigners, we definitely need some international exposure. The question is how much but I won’t get into that here.

Emerging markets

Might emerging markets offer greater returns than more developed countries?

You know how it works by now so let’s go straight to the scoreboard:

Pretty self-explanatory.

The future may be different from the past so I suppose you might have little bit of emerging market exposure just in case. However, going all-in on emerging in order to beat the house would be quite a bet.

In any case, I’ve said my bit on emerging markets.

If you want to delve deeper into the relative historical returns of various countries, check out this page and crunch the numbers for yourself.

Actively managed funds

If you’re a regular reader of this site then you think you know what I’m going to say about this.

Prepare to be surprised.

Passive index funds infamously beat actively managed funds almost all the time, after fees. This is well established.

However, Market Sentiment had a deep dive into the issue and tried to see if there was ever a case where they might win.

I encourage you to read the whole article as I think he makes a strong case, but the Tl;dr is:

Surprisingly, it does look like active management has its benefits if you are willing to put in some groundwork to find the right ones. I still don’t feel that a 0.18% better return over the index in Large Cap is worth it after doing all the research and you will be better off sticking to the index. But, both in the case of Emerging Market funds and Small-cap equities, actively managed funds vastly outperformed their respective index.

For those of you who didn’t read the original post despite my exhortation to do so, he is only referring to a tiny number of funds that have consistently beaten the market over a long period of time, not any old active funds.

I had a quick look at active Vanguard funds I have easy access to and found that none had data going back far enough to fairly judge them.

Personally I’ll just stick with the bog-standard index fund. However, I guess you might locate these super-dooper funds in specific areas and use them as satellite investments to complement your core, broad index fund.

All seems like too much effort to me, plus I’m skeptical that they can keep up the outperformance forever. Return-to-mean is a formidable force and sometimes happens to fund managers when the old tricks they’ve always used no longer work due to changed circumstances. Plus if they’re really good they’ll be demanding higher and higher fees, which may eventually cause those lines on the graph to cross.

I also suspect there’s some survivorship bias here. Let’s say I want to be a world-renowned fund manager. I start a stable of 20 funds. Nineteen die in the arse because I’m an idiot, but one gets off to a good start just by chance. I discontinue the shit funds, keep the lucky one, and hey presto! I’m Warren Buffett. The fund will probably underperform later year-by-year but I can get around that by only displaying cumulative graphs that include those initial, fortunate years that make the returns look better than they are.

I’ve seen it happen but I won’t name names here.

Further, I’m concerned about the tax implications of managed funds that involve more frequent trading than index funds. This will depend on your jurisdiction and other circumstances.

Oh, as as for that magical Medallion graph above? See also:

Renaissance’s Medallion Fund Surged 76% in 2020. But Funds Open to Outsiders Tanked.

My dear reader, you are trying to go faster than the speed of light!

Dividend investing

Let’s compare the S&P 500 to the S&P 500 Dividend Aristocrats, an index which tracks the companies within the S&P that increase their dividends every year:

Not bad. For a while the Aristocrats were beating the house, then they switched, and in recent times they have converged. The Dividend Aristocrats were less volatile so on a risk vs reward basis they seems pretty good.

However, there are some good arguments against dividend investing for those in the accumulation phase. Tax will likely be the biggest concern if it would apply to your fund.

Conclusion: I reckon dividend investing best suits retirees wanting a steady income. For those still in the accumulation phase, the broad index is probably better. Your circumstances may differ so get individual advice, especially tax advice.

We sometimes go around in circles on this issue so please keep in mind before commenting: the fact that dividend investing suits your circumstances does not necessarily mean it suits other people’s circumstances, for the reasons articulated.

Picking your own stocks

Not going to spend much time on this. A few people can do it profitably but the vast majority lose and in any case, the time you have to put into research plus the extra risk are not worth it unless this is your passion.

If pouring over data is not your idea of a fun weekend, stick to the index.

Conclusion

The house is pretty strong, but it nevertheless makes sense to:

Invest in an index fund that’s broader than the S&P 500

Probably have some international exposure, and

Maybe try out one of these whizz-bang managed funds for a little bit of emerging and/or small caps exposure

However, I’m not convinced on 3. One and 2 won’t make a huge difference because both of these correlate strongly with the S&P 500, but are probably still worth it for the extra diversification and may net you a few extra bucks over the long run.

Does the house always win?

Not quite, but close to it. You can probably get a fingernail ahead with minimal effort by following 1 and 2 above.

Always remember, everything we’ve discussed today is way less important than the basics: avoid bad debt, have an emergency fund, budget, save and regularly invest. If you can do that, beating the house is gravy.

Unlike the casino, ‘the house’ here works in your favour anyway and average returns should be enough for you to beat inflation and retire comfortably, so long as your time frame is long enough.

![The Poor Man's Guide to Financial Freedom: A Realistic, 10-Step Manual to Building Liberating Wealth on a Low to Medium Income by [Nikolai Vladivostok] The Poor Man's Guide to Financial Freedom: A Realistic, 10-Step Manual to Building Liberating Wealth on a Low to Medium Income by [Nikolai Vladivostok]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!kZ8a!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F8b92d3b4-ff37-404f-af32-ca618c432e4d_333x500.jpeg)